In 1967, the Tucson School District in Arizona launched what was perhaps the first modern school resource officer (SRO) program. Prior to this, police interaction with schools had been minimal and largely enforcement based.1 In 1953, for instance, police were assigned to schools in Flint, Michigan to check juvenile delinquency as a youth crime panic comingled with racial tension in the town. What was proposed in Tucson was something different, however. Police were not being placed in the schools to prevent crime, but to improve community/police relations.

Those in Tucson supporting the introduction of police into schools assured parents that “the school detective is not a replacement for the school counselor” and that school resource officers “are not permitted to take disciplinary action.” Citing the introduction of detectives in Atlanta schools, they write that the function of police in school is to “promote good citizenship among students, foster an attitude of respect for the personal and property rights of others, cultivate within students a spirit of law observance.”2

Still, many in the community were skeptical of these claims and the SRO program was met with immediate resistance. Local ACLU officials warned about the “unlimited discretion” being offered to school resource officers to interrogate students/minors without an adult present. In an editorial published in Christian Century, the ACLU warned:

The craving for security makes well meaning people vulnerable to schemes which promise order and security but which demand payment in sacrificed rights… Thus in Tucson well-intentioned people put their junior high school children under police surveillance to purchase ‘a better understanding of law enforcement and to prevent juvenile delinquency.’3

A group of concerned parents and educators formed the Citizens Committee for Discussion of SRO and expressed their concern:

The detection of anti-social and criminal tendencies is properly the function of trained and certified teachers, guidance counselors, social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists. The chief responsibility for prevention rests with the family. To shift any of the burden from the home to the school is to go part way in the abridgement of parental authority and obligation. But for the school, which employs trained personnel, to pass responsibility on to the police – an alien, untrained authority – the armed friend who is suddenly the official inquisitor – constitutes an unconscionable abdication of authority.4

The Citizens Committee concludes, “we oppose, on principle, the introduction of the police into education.”

A year later, the Citizens Committee on Respect for Law, Self-Discipline and Morality in Pasadena proposed the creation of a school resource officer program for their middle schools in order to “develop closer rapport between students and law enforcement officers and to create greater respect for law and order.”5 By 1969, several other school districts in and around Los Angeles created their own SRO program proposals.

Since the uprising against police violence began in Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis PD, it has spread to every city in America and to a dozen other countries. People, no longer pacified by the liberal mantra to “vote blue no matter who” and given no other avenue for justice in America, have taken to the streets and are finally getting a taste of actual political power.

The officer who killed George Floyd was arrested and charged only after protesters burned down the Third Precinct police station where he worked. His fellow officers who participated in the murder were only charged after three more days of militant protesting. Here in Seattle, protests forced the city to rescind its petition to have SPD released from federal oversight. Across the country, concessions that were deemed “politically impossible” after the Ferguson uprising in 2014, such as disarming and defunding the police, are now being talked about seriously in many quarters.

In Minneapolis, the school district has finally assented to a decade of demands to cancel its contract with Minneapolis PD. An agreement that created a permanent occupying force of police in Minneapolis schools. Portland schools soon followed and, as of writing, Denver is voting on a similar measure.

As police lose lucrative school contracts, contracts that drive money away from schools and into the carceral state, you are likely to see a lot of media handwringing about “safety” in schools and mass shooters. This plays on the common fiction that police were put into schools as a safety measure after the shooting at Columbine High School in 1999. The reality, is something entirely different, however.

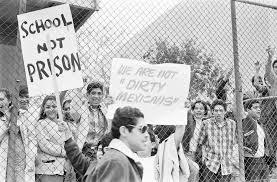

Student protesters during the East LA walkout in 1968

Part I: The Velvet Glove

The Beginning

On March 5th 1968, a series of student walkouts began involving a half dozen Los Angeles high schools. It was the first student walkout in the LA Unified School District’s 113 year history. Students had been leafletting for the walkouts for more than a month and there had been an attempted walkout the previous week. “The shrill voice of dissent shattered the educational calm,” Johns Harrington, head of the LAUSD Division of Instructional Planning, later recalled.6

The walkouts were part of the growing Civil Rights Movement and anti-Vietnam War activism that was sweeping the country and focused on challenging LAUSD’s racially segregated school system. Students carried signs reading “No More Fences” (around the school), “Smaller Class Sizes,” “Chicano Power,” and “Viva la Revolucion!”7

Initially, the walkout included five high schools, but it rapidly expanded to four more high schools and two junior highs involving thousands of students. Students fought pitched battles with police in the streets. Robert Sanchez, a student at Roosevelt HS: “If I could be allowed to express myself with dignity, I’d do so. But if they’re grabbing me, or hitting me, and there’s a rock or a brick there, I’d throw it.”8

Police were deployed to schools all over Los Angeles to quell the insurrection. The students issued a list of demands to the press:

- More bilingual instruction

- More Mexican cultural heritage in curriculum and textbooks

- Smaller class sizes

- Firing racist teachers

- More liberal dress code

- Removal of restrictions against black students wearing their hair in “natural cuts”

- Improved cafeteria conditions

- More student rights

- Protection against search and seizure from HS staff and the ability to bring complaints against teachers and other district employees

John Ortiz, representing students from Garfield HS, added “We will not have a special session [with the school board] until the police are removed from campus.”9

The school board denied that they had the ability to remove LAPD from their campuses, kicking the decision down to the school principals, who also claimed they couldn’t do it. When parents approached the LA District Attorney Lynn Compton to demand the removal of police from campus, Compton told them that she could not do anything about it.10 LAPD was essentially accountable to no one.

Police continued to attack and beat students both in and outside of their schools. After police issued a tactical alert to break up a crowd at Roosevelt High School, Richard Avila, president of the Mexican-American Student Association told reporters, “The Mexican American Student Assn. was informed that the walkout was going to be so well organized that ladies from the community would serve sweet bread and coffee to the kids when they walked out. But when the kids actually walked out, there were no ladies with sweet bread and coffee waiting for them. The only reception they found was an army of police who had been prepared for such an eventuality for weeks.”11

Police blamed “outside agitators” and “professional agitators” for the student walkouts.12 At Roosevelt HS, 101 teachers signed a petition blaming the unrest on “a small militant faction” of students. Ray Ceniceroz, the Garfield HS faculty chair, was more introspective: “We feel disturbed and ashamed that these kids are carrying out our fight. We should have been fighting for these things as teachers and as a community. Apparently, we have been using the wrong weapons. These kids found a new weapon—a new monster—the walkout. If this is the way things are done, I’m just sorry we didn’t walk out.”13

While the LAUSD school board discussed whether they should meet with students more than a week after the walkouts had started, school board member Julian Nava summed up the situation, “Jack, this is BC and AD. The schools will not be the same hereafter.” To which, the LAUSD superintendent of public schools Jack Crowther responded, “Yes, I know.”14

The walk-outs in LAUSD prompted an immediate reaction in the suburbs. In Pasadena, a group calling itself The Citizens Committee on Respect for Law, Self-Discipline and Morality, began the 1968 school year demanding that Pasadena adopt a school resource officer program for its middle schools. “The purpose is to develop a closer rapport between students and law enforcement officers and to create a greater respect for law and order.”15

In Glendale, Police Chief Duane Baker proposed the adoption of an SRO program for the middle schools in the Glendale Unified School District. In language remarkably similar to that used in Pasadena, Baker described the program, “The work of the officer will be to promote rapport between students and law enforcement… and help students develop an understanding of society based on law and order.”16

City counselors in Pasadena, Glendale, and Pomona all voted to approve the new school resource officer programs. The relationship between the program and the community’s fears around the Civil Rights Movement were made especially clear in Pasadena. Police for the SRO program were pulled from the community relations division that the police department had created after the 1967 uprising that began in Watts and eventually spread all over the LA area.

In 1968, a class action suit was filed against the Pasadena School Board seeking to desegregate the city’s schools. Joseph Engholm, president of the Pasadena Board of Education went on a tirade when the NAACP presented the school board with evidence of discrimination. Engholm demanded that black students and their representatives first condemn “black violence” before he would hear any complaints about discrimination, going on to scold the students, “When are you going to stop yelling ‘prejudice’ every time a Negro student is disciplined.” He then criticized the black students for white flight from LA and Pasadena. When members of the audience accused Engholm of racism, he assured them that “My wife and I entertain our Negro friends.”17

In March of 1969, 200 black students at Pasadena HS protested the creation of an all-white “song leader group” at the school. When the school refused to hear the students, they began a picket at the school. The picket was quickly joined by two nearby middle schools. Black students at Muir HS joined in demanding a Black Student Union on the campus. When the school board refused to meet with students from Pasadena HS, a third high school in Pasadena joined the picket.18

Students argued that only white students are allowed into college preparatory classes and that black and Latin students are physically segregated into just two buildings on campus. Students demanded more minority faculty, the right to form student groups, and the inclusion of Mexican-American history into the curriculum.

Board members claimed that this was the work of outside agitators. Board member Elmer Wallace read a report claiming that the protests were the work of the Pasadena Commission on Human Need and Opportunity and the Pasadena Westside Study Center. The report claimed that these anti-poverty orgs were really just drug dens that should be defunded and investigated. When students demanded to ask the report’s author, Besse Licher, questions about the findings, Licher responded angrily that she “would not be put on the stand for cross examination.”19

In 1970, a federal judge ordered the Pasadena Board of Education to develop a plan to begin desegregating its schools. Later that year, the Board voted to expand the SRO program to deal with “student unrest.”20

LA became the first major metropolitan area to adopt modern school resource officer programs in a mass way. What was initially proposed in Tucson and carried out in LA was the permanent stationing of police officers in schools for the express purpose of propagandizing students and the implied purpose of keeping troublesome ideas like civil rights and anti-war activism off of school campuses.

The Reaction

Early police-in-school programs targeted junior highs where the students were deemed easier to reach.21 Parents were assured the programs were “purely educational” and their intention was “not to effect a policing plan.”22 “In no way,” Arden Daniels, a Glendale school principal, emphasized in 1970, “does he [their SRO] participate as a disciplinarian, a responsibility of the principal and other administrators.”23

The purpose of these early programs was to “develop a closer rapport between students and law enforcement officers and to create a greater respect for law and order.”24 When Monrovia mayor Richard Mountjoy proposed an SRO program for Monrovia HS in 1972 after clashes over integration, he boasted SRO’s would “create a favorable environmental climate in which to teach a greater respect for law and order and understanding of law enforcement.”25

Essentially the police were there to serve a propaganda and normalizing function. It was an early form of community policing. “Community policing,” police researcher Kristian Williams writes, “helps to legitimize police efforts by presenting cops as problem-solvers. It forms police-driven partnerships that put additional resources at their disposal and win the cooperation of community leaders. And, by increasing daily, friendly contacts with people in the neighborhood, community policing provides a direct supply of low-level information. These are not incidental features of community policing; these speak to the real purpose.”26

Los Angeles became a petri dish for modern policing tactics. The SRO program in Los Angeles became the palatable velvet glove to SWAT’s iron fist.

Early efforts to institute this new policing model in schools were met with strong community resistance in many cases. In March of 1969, students at Plainfield, New Jersey’s Plainfield HS led a walk out to protest racial discrimination in the school. The school district called in the police to occupy the school and put down the walk out.

Students agreed to end the walk out if the police were expelled from the school. The school administration reneged on the agreement, prompting parents to mass outside the school shouting “sellout!” and “Get the Gestapo out of here!” Administrators tried to assure parents and students that while they had three Pinkerton guards for security, the police in the school were only for “communications.”27

At 10:15am, the students walked out again.

After the walk out, the New Jersey State Board of Education requested that each school district submit “its specific plan for coping with potential student disorder.”28 More than 500 plans were submitted with all but one of them involving the police. The most popular strategy for dealing with student disorder was “to use the threat of police involvement as a lever to disband the students,” appearing in 43.8% of the plans. Seeking out the cause of the disorder by meeting with disaffected students appeared in only a third of reports.

While parents and students might have disapproved of the police presence in schools, it was clear that administrators were beginning to see it as a useful tool of social control.

A pitched battle over the presence of police in schools took place in Berkeley, CA when Berkeley police wrote a proposal for an SRO program for Berkeley HS. Officers were assigned to four campuses in September of 1973, but were pulled off the campuses two weeks later when it was discovered they were carrying guns.

Berkeley PD pushed to have the program reinstated. Students at Berkeley HS held a vote on the issue with:

- 994 voting against having any police on campus

- 684 voting for having unarmed cops on a trial basis [something the police considered non-negotiable]

- 224 voting in favor of the SRO program29

Anger over the program amongst students was such that Berkeley student Jeff Raz told reporters, “Cops on campus would probably mean a strike.” Another student, Denise Minafield stated, “The police attitude seems to be that it isn’t a matter for students or their parents, and if the School Board rejects the idea, then they’ll do it over the Board’s head.”

Students held a large rally demanding “No cops on campus.” Eventually the pressure was such that the School Board voted unanimously to end the program.30

In that same year, the Board of Education in Franklin Township, NY agreed to start an SRO program telling parents, “The primary task of the policemen… will be to establish positive contact between the police and young people… School officials stress that the School Resource Officers will not patrol the halls or discipline the students on their own.” They will only report disciplinary infractions to the proper school officials.31

Parents and students became increasingly concerned that School Resource Officers would be bringing guns on campus. The school board tried to re-assure parents that while officers will be armed – something the police considered non-negotiable – they would “perform law enforcement functions only if imminent danger threatened.”32

This was cold-comfort for parents and students, and the Somerset County ACLU quickly became involved in opposing the SRO program. Opponents argued that the program violated the state’s Administrative Code by allowing school staff to bring guns into the school. The School Board countered that the police were exempt from this law because they were being paid by the police department and were not in fact school employees.

Eventually, pressure from parents and the legal threat being posed by the ACLU forced the school board to drop the SRO program. In scuttling the contract with the police department, the board cited the weapons controversy and the “almost unlimited access” that SRO’s would have to student’s records “for unspecified purposes.”33

Boston Busing Crisis

In 2018, Police Magazine put out an issue titled, “SPECIAL REPORT – Keeping Schools Safe” advocating for the expanding role of law enforcement in school. Prior to issuing the report they sent out a write-in survey to their 43,000 police subscribers asking, “What measures would you take to prevent school shootings or improve response to them?” The second most popular response – just behind ‘know ahead of time who is going to do the shooting’ – was broadly categorized as “harden the target.”34

Respondents suggested, “Schools should reduce the number of ingress and egress points used by students and staff and set up metal detectors and video surveillance to monitor who is coming in and prevent them from bringing weapons with them.” They go on to suggest creating a TSA for schools, charged with checking student IDs and searching kids at the doorway, giving teachers panic buttons, and putting drop down barriers in hallways to isolate students in a crisis.

Now if you went to a public school in the last 30 years, you will be aware that most of this stuff already exists in a lot of schools. But the fact that the conversation around turning schools aesthetically and functionally into prisons has become completely normalized is a victory for the SRO program.

In 1982, the New York Times described Brooklyn’s Jefferson High School as “surrounded by empty lots and mountains of trash in one of the most destitute sections of the city. It is regarded by school officials as one of the most dangerous of New York’s schools.”35 Naturally, in the midst of its neoliberal rebirth, the city saw the conditions at Jefferson HS as requiring more policing rather than more social services.

In November, the school board ordered the use of handheld “airport style” metal detectors to be used at the entrance of the school to check every student. Students questioned the searches, arguing that it was a violation of their rights. The administration maintained that students had no rights.

Searches began at 8am, one student who was searched multiple times before being accused of having a weapon was “literally picked up and carried to the dean’s office.” Two hours later, students were leaving the classroom and walking out of the school en masse. For more than two hours police clashed with students in the streets as students shouted “Gestapo tactics” at police and school security. The school board temporarily suspended its use of metal detectors.36

Looking back from the hyper-policed and hyper-surveilled present, it can be difficult to understand the unease with which people responded to things like metal detectors. When the use of metal detectors at airports was first suggested in 1961, the FAA came out in staunch opposition. Quoting historian Ryan Archibald on the FAA’s testimony to Congress, “While useful in weapons and defense factories, and federal prisons, or as devices for labor discipline and penal institutions, metal detectors would be an imposition for the urbane ‘jet setter.’”37

When metal detector use was finally introduced in airports in the late 1960s, it was opposed by civil liberties groups as an unwarranted search by authorities. In the 1971 federal court case, United States v Lopez, the court had to “reterritorialize” the airport and claim that it was an international border where Fourth Amendment protections do not exist in order to justify the searches. 1972’s United States v Epperson further eroded the right against search and seizure by claiming that Fourth Amendment protections do not apply to metal detectors since their use is not a “annoying, frightening, or humiliating experience.”38

Their use was touted as a dispassionate and equalizing tool of law enforcement, though even that was questioned at the time. In 1972, a reporter for Popular Mechanics jammed his suitcase full of metal and proceeded to walk through a metal detector and board a plane without being stopped. The author, who was white, believed that he succeeded with this because he “did not look suspicious.” “If you have a dark-skinned swarthy appearance, are shabbily dressed, wear long hair, act nervous, or otherwise look suspicious you may be questioned.” However, should you be “the average well-scrubbed, neatly dressed tourist or businessman, the chances are that you won’t.”39

The racial context in which metal detectors were introduced in schools is best illustrated by the struggle over school integration at South Boston HS. In 1974, a federal court ordered that a plan be drawn up to desegregate the Boston school system. A decision was made to concentrate busing in the poorest neighborhoods of the city, with white students from South Boston and black students from Roxbury busing between schools.

Busing in Boston was met with immediate resistance from white residents in South Boston who pelted school buses transporting children with bricks. Resistance to busing wasn’t just the province of poor whites in south Boston. In December of 1974, the Boston School Committee voted 3-2 refusing to implement the federal court ruling.40 Louise Day Hicks formed the group Restore Our Alienated Rights, or ROAR, an openly racist group that met at City Hall. Hicks was a former MA representative in Congress and served as president of the Boston City Council for the majority of the busing crisis. Former metal worker, James Kelly would create the South Boston Information Center where much of the antibusing fight was organized on the ground.

President Gerald Ford even spoke out against school integration, now that it was being done in the North, telling Boston reporters during a visit, “I have consistently opposed forced busing to achieve racial balance… and therefore, I respectfully disagree with the judge’s order.” The Boston Globe, noted that, “it was clearly not a quick, off-the-cuff statement. His remarks added up to an answer for which the president had been briefed before the conference.”41

In 1976, Jimmy Carter would add his own two cents to the integration debate telling supporters that he did not believe that the federal government should do anything to change the “ethnic purity” of city neighborhoods or the “economic homogeneity” of the suburbs.42

In October of 1974, metal detectors on loan from airlines were introduced at Hyde Park HS and South Boston HS after a white student was stabbed at Hyde Park. The stabbing had occurred in the greater context of violence around busing in Boston. A week prior to the incident, a black driver whose car had stalled near South Boston HS was beaten by a mob of white residents. A week after the stabbing, another black motorist was pulled from his truck and beaten by a white mob blocks from South Boston HS.43

Inside the schools, dozens of fights between black and white students were reported daily at South Boston and Hyde. In December, a white student who had been in several previous altercations with a black student was stabbed, this time at South Boston HS. A crowd of 1,000 white Bostonians surrounded the HS, trapping the 135 black students in the school for nearly four hours as State Patrol tried to clear an escape route.44

As the violence continued to escalate in South Boston, Judge Garrity, who was overseeing the busing order, put South Boston HS into receivership for the 1975 school year. The next day, white protesters firebombed the local NAACP office.45 When Jerome Winegar was brought in from Minneapolis to run South Boston HS in April of 1976, he was greeted with a large “Jerome go home” sign on the front door of the school.46 “Authorities,” Winegar later recalled, “gave us no support. I was introduced to no one. But I was assigned a bodyguard. I stayed in a hotel and went to school with a police escort.”47

Violence spread throughout the city. A woman who volunteered to be the first black person to move into a South Boston housing project had her car firebombed. She moved out shortly after. In Italian East Boston, a black family had their apartment firebombed. A black high school football player for Jamaica Plain HS was shot in the neck while standing in the huddle on a football field in South Boston. The student, Darryl Williams, was left paralyzed.

In 1979, an exasperated Jerome Winegar told reporters, “I can’t believe that not a single politician or government leader has spoken out in any way. This is the craziest place I have ever been,” before going on to say, “I’m afraid this city just isn’t going to make it… the haters have proved that hate is stronger than love. We are very depressed.”48

This is to say that the context in which metal detectors were introduced was one of hyper violence in the city. It could be easy to see the need for the devices. But Winegar actually took a different approach. A 1979 LA Times’ profile of Winegar and the busing crisis in Boston is worth quoting at length:

One change was the police presence in the school. During the first two years of desegregation, state police officers were stationed every 10 or 15 feet in the hallways, and civilian aides were also assigned to the schools, so that there were days when more adults than students were in the building.

All that show of force had not helped maintain order. It seemed, if anything, to work against it. Classes were frequently suspended during the first two years. On either side of the main lobby, two rooms were kept aside as holding pens for unruly students—one for whites, one for blacks—and they were often full.

Winegar got the policemen out of the school, slowly phased out the use of weapons-hunting metal detectors at the doorways and stopped the wholesale suspensions of students involved in disciplinary problems. He developed an “in-school” suspension program that kept the students in the building, but separated from students in regular classes for short periods.

“What good does it do to toss a kid back out on the street?” he asked. “When he comes back—if he comes back—he’s probably going to be an even worse problem.”

Meanwhile, Mrs. Kozberg set about making changes in the curriculum and devising programs that would keep students in school and lead them somewhere afterward…

A day at South Boston High School… provided a picture that was far different from the lingering image of Southie as a virtual prison for teenagers.

Students entered the building noisily, as students do anywhere, but without any trace of hostility between blacks and whites. Although the buses rolling up to the school—a double file of 10 buses, a police car in front and back—was a reminder of past tensions, the students seemed accustomed to the spectacle to the point of taking virtually no notice.

By demilitarizing his school, Winegar appeared to be calming the racial tensions within its walls. Something that anti-busers could not tolerate.

It was only a few days before that visit that the first incident occurred in Boston’s latest trouble. A group of white youths, some wearing ski masks to hide their identity, assaulted some of the buses just before they reached the school.

At that point, Winegar, who had said very little in public since coming to the school, assailed the city establishment, its clergy and politicians.

“I never said anything before because I had no credibility,” he explained later. “I believe you have to choose your time, and that was my time.” Winegar’s ire was directed particularly at Boston’s politcians, then in the middle of a primary election campaign.

A few days later… a black football player from Jamaica Plain High School was shot in the neck as he stood in a huddle with his teammates on a field in Charlestown, another all-white neighborhood that has strongly—and sometimes violently—opposed busing.

The student, Darryl Williams, 17, was left paralyzed from the neck down. Police later arrested three white youths in connection with the shooting. And since then, the tension in Boston high schools has mounted almost daily, reaching its peak—thus far, at least—last week when Winegar was forced to shut down Southie for the first time in his tenure there.

Winegar, along with some other persons in the community, has strong suspicions that white adults, the people he refers to as “the haters,” were behind the first attack on the buses approaching South Boston High. He said that he learned of the identity of the youths involved in the attack “10 minutes before it happened,” that some students “told me they were at a meeting where the whole thing was planned and that there were adults at the meeting…”

Some observers here are now speculating on the role of Boston politics in shattering two years of relative calm in the schools. Mayor Kevin White, running for a fourth term this year, seemed to have effectively quieted his long-time opposition in South Boston this year by placing several key antibusing activists on the city payroll. One of them, James Kelly, the head of the antibusing South Boston Information Center, was appointed to an $18,000-a-year job in a city development agency.

Although Kelly steadfastly denies that there was any connection, election posters for White suddenly blossomed all over South Boston, joining such neighborhood favorites as City Councilman Ray Flynn and Louise Day Hicks…

Mayor White had never before carried an election in South Boston. This year, with antibusing forces seemingly quiet and some key City Hall jobs spread around the neighborhood, he seemed to have a good chance.

Then the liberal community began to hound White about Kelly’s job. Several days before the election, Kelly resigned, but the conventional wisdom in the neighborhood was that he was forced out.

Then, on September 18, one week before the primary election, came the attack on the buses at South Boston High.

Kelly… becomes incensed at any suggestion that links him, Boston politics and the trouble at Southie…

“All this is,” he went on, “is just a lame excuse they use because busing has failed in Boston. There is no conscious effort on our part to shut down South Boston High School. But if someone came to me and said, ‘You are going to be indirectly responsible for closing the school,’ well then, I say, let it shut down. If the school closes, it’s not going to be because of anything Jim Kelly has said or done, it will be because busing has failed.

“You have to realize,” he concludes, “that we are going to win. There is absolutely no way they can silence us.”49

Early in the 1980 school year, James Kelly organized a boycott of white students at South Boston HS, demanding that metal detectors be re-installed at the school. John O’Bryant, the only black member of the Boston School Committee, criticized Kelly’s demand for metal detectors as “a racist statement because it infers that only black kids bring weapons to school.”50

“It would be a big mistake to go back to metal detectors,” Winegar told the press, “We’re not running a concentration camp here.” After two weeks, Kelly called off his boycott.

In 1987, Judge Garrity handed over control of the Boston school system back to the Boston School Committee. The School Committee immediately began dumping students into South Boston HS while cutting its budget to the bone. Kelly’s South Boston Information Center began leading a campaign to have Winegar fired. In 1989, Winegar was fired.51

In 1993, at the urging of James Kelly, who now served as the City Councilor for South Boston, the city’s mayor re-introduced metal detectors to South Boston HS. Quoting the New York Times:

In an interview, James Kelly, the white City Councilor who represents South Boston, blamed blacks for the racial tensions in his district. "They're going into mom-and-pop stores and taking whatever they want," he said. "You get 15 black males who all look like Mike Tyson's brothers, and there's one merchant. Is he going to say something to them? No."

Mr. Kelly attributed fear and tensions in the high school to black students, "a good portion of whom act like a bunch of terrorists."52

While the battle over “hardening the target” at South Boston high school raged, something else was going on in American public schools that helps explain why they increasingly took on the aesthetics of a prison.

It is no coincidence that schools adopted this more carceral approach to student discipline at the exact same time that white students and parents began fleeing the public school system. Efforts at desegregating schools in Boston led to white families fleeing to the suburbs or to private schools – 85% of public school students in the city are now non-white.53

In the South, “segregation academies,” religious private schools designed to maintain school segregation, continue to flourish long after school busing has faded from the scene.54 In Philadelphia, white flight from public schools left one teacher asking in 2005, “Where have all the white kids gone?”55 The Harvard Civil Rights Project notes that the trend toward desegregation in schools reversed itself in 1988 leaving many schools more racially segregated today than they were in 1968.56 As a result, in 2014, for the first time in the nation’s history, the majority of kids in public school were non-white.57

The changing demographics of American public schools has several implications. First, because of the deep and historical connection between race and class in the United States, news of the racial demographic swing in public schools was followed quickly by news that the majority of public school students are poor.58 As one would expect, defunding of the public school system soon followed.

It is a disturbing trend in the United States that once a public institution becomes associated in the public mind with poor people and, most importantly, black people, support for maintaining that institution begins to wane. Welfare was eviscerated with the aid of a concerted campaign to associate the program with poor black mothers in the eyes of the public. Similarly, public education is increasingly associated with the urban poor, driving up support for private school voucher programs and charter school “alternatives” that drain vital resources from public schools.

Finally, the demographic change in public schools makes it easier to shift from an education model in schools to a carceral model—and to accept the violence that comes with it. Schools with SROs that encourage a zero tolerance disciplinary model increase the level of interaction between students of color and police. Sadly, this leads to predictably disastrous results.

Part II: The Iron Fist

On an early November morning in 2003, students at Stratford High in Goose Creek, SC milled around the school’s hallways and cafeteria waiting for the school day to start. Their morning routine was shattered, however, when police in SWAT team armor suddenly burst out of utility closets and stairwells with guns drawn, screaming at them to get on the ground. Terrified, some students froze in place while others ran for cover.

Black students in particular were the targets of intimidation and arrest. The principal, George McCrackin, coordinated with local police, timing the raid so it occurred just after the buses transporting students from predominantly black neighborhoods arrived. And two-thirds of those arrested were African American. As Jessica Chinners, a white tenth grader, said, “I looked down the long hall and saw the police lining up all these black students.”59

While police “secured” the school, McCrackin personally accompanied officers through the cafeteria, pointing out students he thought should be arrested. Teenagers were removed at gunpoint with their hands zip-tied behind their backs while police dogs sniffed them for drugs — none of which they found. “I really don’t know why they did what they did to me,” Rodney Goodwin, a black tenth grade student, later told reporters. “I didn’t do anything wrong, but they arrested me.”

Video of the raid was leaked online, sparking outrage. In a letter to parents McCrackin attempted to exonerate himself: “I was surprised and extremely concerned when I observed the guns drawn. However, once police are on campus, they are in charge.” While McCrackin failed to mention his crucial role in the raid, his comment did highlight a stark truth about police and schooling: once cops are on campus, they are in charge.

In 1985, psychologists SV Phillips and R Cochrane, listed the five objectives of an SRO program:

- To improve the police image

- To inform students about what police do

- To make young people aware of dangers

- To inform students about the law and the rights and duties of citizens

- To develop a sense of social responsiblity60

In October of 1982, more than 250 students from Miami’s Hialeah and Miami Springs high schools were enjoying a skip day at a local park. According to the Miami Herald, students were setting out food, tossing footballs, and chugging beer when police arrived. Police blocked off the parking lots that students were parked in and had four school buses brought in for transport.61

“It was like bringing cattle in,” school resource officer Barney Silver told reporters, “We pretty much rounded them up.” Students were transported to a local middle school for “processing” where many tried to escape out the back door. Those that remained were brought to their respective principals to face the music.

Three months later, parents from Hialeah HS demanded that the city add four more SROs to the high school.62

Early in the adoption of SRO programs, many parents expressed concern about police serving the role of enforcer inside a school. There was a general sense that an armed agent of the state with a literal license to kill was the inappropriate vehicle for disciplining children.

The Reagan Era provided the perfect environment for transcending that fear. Police were feeling themselves with the new law and order president in charge. And federal cuts to education spending spread to the local level leaving schools strapped for cash. Keeping attendance numbers high became critical to getting scarce school funding, and administrators were willing to accept an expanded role of the police in order to get it done.

In 1985, the Glendale School District on the outskirts of LA built a “detention center” in their administration building to accommodate students rounded up in monthly truancy sweeps. Students were handcuffed, taken to the facility where their parents retrieved them, and then punished by the school administration. School resource officers worked with local police, giving intelligence on where to engage the sweeps.63

In 1987, school officials declared the program a success having boosted attendance from 97.2% in 1985 to 98.4% in 1987. Others remained skeptical. One student who was picked up on the way to school told reporters, “This is so stupid! So stupid! We were going in the direction of the school when they picked us up… I’ve missed four classes now. When they picked me up, I hadn’t missed any classes.”

These sweeps raised a variety of issues. When questions came up regarding a police officer’s right to stop and question people that they believed to be school age, the California state court ruled that Fourth Amendment rights could be suspended during school hours.

There was also the issue of what exactly the sweeps accomplished. The minor uptick in attendance meant a marginal increase in school funding, but much, if not all, of that funding was immediately eaten up by the cost of the SRO program. When Glendale first adopted an SRO program in 1969, it was federally funded for a three year pilot period. After which, the district and the police department split the bill.64 In short, truancy sweeps became necessary to fund future truancy sweeps.

Thirdly, came the question of what happens when you put police in contact with children. While it is obvious that police have to come into contact with an individual before they brutalize or murder them, that fact is not always translated into its obvious corollary, that any contact with police carries with it an inherent risk of violence. Maybe people could ignore this potentiality when police were getting their kicks breaking up teenage beer-busts in the park, but a youth panic was growing in America.

The Youth Panic

“Kids are coming to school with Uzis!” Oprah Winfrey told her audience in 1988 as she stood in the gym of Southwestern High School in Baltimore. “Kids are hiding guns in their underwear! Knives in their socks!” Flanked by police and security guards, Oprah would not even enter the school until metal detectors were installed. Baltimore’s mayor, Kurt Schmoke, had resisted calls to put metal detectors in schools, saying that they would make the schools “an armed camp.” So, Oprah brought her own, joking on the show, “I brought my own security.”

According to the LA Times, “Security was very, very tight. There were uniformed police and security guards in military dress. And everybody had to walk through a metal detector. Oprah may have come to report on school violence, but she did not want to be a victim of school violence.”65

A hysteria around youth and crime was gripping the nation. Reviewing the 1990 exploitation flick, Class of 1999, in which student gangs engage in open warfare at Seattle’s Kennedy High School until Terminator-style cyborg teachers arrive on the scene to restore order, LA Times movie reviewer Kevin Thomas described this absurd scenario as “uncomfortably close to the possible.”66

The youth panic was fueled in part by Reagan’s amped up war on drugs. Reagan’s first drug czar, Carlton Turner, revealed the political motivation of the drug war when he stated that marijuana was a gateway to “the present young-adult generation’s involvement in anti-military, anti-nuclear power, anti-big business, anti-authority demonstrations.”67 Prosecuting the drug war helped correct, to quote conservative academic Samuel Huntington, the “excess of democracy” that characterized the late 1960s.68 There was a reactionary right wing wave sweeping the nation and youth, particularly black and brown youth, were in the crosshairs.

The 1989 Central Park jogger case, in which a young investment banker was raped and severely beaten as she ran through Central Park, saw this youth panic boil over.69

The case quickly became a media circus as the New York police speculated in the press about gangs of black youth were terrorizing people in the city. NYPD Detective Robert Colangelo even came up with a name for a “new game” teenagers were purportedly playing: “wilding.” Like it’s more recent analog the “knockout game,”70 wilding was a racist myth. But the media ran with it.

Five teenagers (four black and one Latino) were quickly arrested, tried, and given long prison sentences. After spending years incarcerated, the defendants’ sentences were vacated in 2002 when a serial rapist — not the five boys — confessed to committing the crime. No gangs, no wilding.

The Central Park case didn’t lose its potency through the 1990s, continuing to fuel a wave of panic about minority youth violence. Writing in the Weekly Standard political scientist John Dilulio coined the term “super-predator” to describe black urban youth “who pack guns instead of lunches . . . who have absolutely no respect for human life and no sense of the future.” Dilulio quoted anonymous district attorneys who warned of kids who “kill or maim on impulse without any intelligible motive” and predicted an oncoming crime wave perpetrated by these super-predators.71

Headlines like “The Criminals of Tomorrow,” “Kids Without a Conscience?” and “Should We Cage the New Breed of Vicious Kids?” filled newspapers and magazines.

This panic served as an excuse for expanding the role of police in schools. Talking to the LA Times in 1992, Paul Walters, police chief for Santa Ana, CA, outlined the expanded role of the school resource officer, “a special relationship is created between the department, the school administration and the students. Officers help the school in identifying potential problems on campus and in the surrounding neighborhoods.”72

As we all know, teenagers have always had problems. In the past those disciplinary issues had largely been considered the domain of parents and school faculty—a boundary that police initially respected. That boundary was chipped away at piece by piece; allowing the police to carry guns in schools, using police to search students, and bringing them into the disciplinary process by involving them in truancy enforcement. Now, school resource officers represented the bridge between schools and the criminal justice system.

“A good SRO is a teacher, counselor, and cop,” Jim Corbin, president of the National Association of School Resource Officers, told reporters in 1993. “And I like to see them constantly changing hats between the three.”73 The hat that police were increasingly wearing was cop, however, as SROs began referring scores of students for prosecution.

And this was not just in the large cities that had been painted as urban warzones. In Hillsborough, FL, just outside of Tampa Bay, SROs referred 247 cases for prosecution to the local DA in the 1991 school year.74 In the Dallas suburbs, 540 criminal citations and 139 language charges were filed against students in two years. A student at Azle HS, just outside of Fort Worth, was charged with disorderly conduct for cursing in class.75

The anti-gang hysteria whipped up by politicians and the press in the 1990s led to the further expansion of the role of police in schools. Hollywood turned inner-city schools with majority-minority student populations into dystopian battlegrounds in films like Only the Strong (1993), Dangerous Minds (1995), The Substitute (1996), and 187 (1997).

This propaganda campaign was extremely effective. A 1996 poll of parents with children in Texas schools found astonishing dissonance in people’s perception of school safety.76

- 78% of Texans thought violence on school grounds was a problem

- 79% of Texans believed their child’s school was safe, however

- 27% of Texans thought violence was a problem on their child’s campus

It was an astonishing dissonance that is in large part explainable by the clear targeting of black youth in the discourse around youth crime. Schools had re-segregated since the 1960s, meaning that parents from the suburbs could be whipped into a terror about school violence even though their schools remained very safe. They simply imagined the violence was happening over there. But in the end, it led to the expanded role of police even in suburban schools and the continued white flight out of the public school system.

Talk of “super-predators” and “kids without a conscience” drove a bipartisan wave of legislation that sought to “bring them to heel”77 by aggressively criminalizing black and brown youth. Mandatory minimum sentences were toughened while the barriers for trying children as adults were relaxed—dropped to 14 in most states.78 Despite (or perhaps because of) the disastrous effects79 of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act on poor and minority communities, its primary authors and promoters (the Clintons and Joe Biden)80 remain the leading voices of the Democratic Party today.

Not as well known, but no less problematic, was the passage of the Gun-Free Schools Act in 1994. Initially designed to create a zero tolerance policy for students caught with a firearm, it quickly crept into every aspect of school discipline.

Law professor Jason Nance notes that schools began to “appl[y] zero tolerance to a multitude of offenses, including possession of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco; fighting; dress-code violations; truancy; and tardiness [emphasis added].” Nance concludes that the presence of SROs “leads school officials to redefine lower-level offenses as criminal justice issues rather than as social or psychological issues… In other words, SRO programs appear to facilitate a criminal justice orientation to how school officials respond to offenses that were once handled internally.”81

It is important to consider the effect that this level of police control has on students. SRO programs socialize students for an over-policed world, normalizing it. Sociologists Aaron Kupchik and Torin Monahan describe the effect of these programs in a 2006 paper, “Police interact with students on a daily basis, cultivate informants, spread an ambiance of control and streamline the formal disciplinary process to efficiently usher students into the criminal justice system.”82

In the name of the War on Drugs, the punitive gaze of police was extended to every student in schools where SROs operated.83 In Kansas City high schools, signs at the entrance of the student parking lot alerted commuters that merely parking implied consent to vehicle searches “with or without cause.” Unannounced, suspicion-less locker searches along with the use of drug-sniffing dogs became staples of school anti-drug programs.

The use of undercover police officers in high schools leapt from the television screen to reality in many cities. One such officer in Atlanta explained his job to a local journalist, “I knew I had to fit in, make the kids trust me and then turn around and take them to jail.”84 The article does not say whether the officer ever considered the negative effect his operation might have had on social ties within the student community.

The School Shooter Bonanza

Throughout the 1990s, school policing remained intertwined with school defunding schemes and the growing obsession with zero tolerance policies. In his book, The End of Policing, Alex Vitale describes the situation in Texas:

At the epicenter of this transformation is Texas, where privatization and drastic cuts to the public sector meet the expansion of punitive mechanisms of social control. Texas was an early adopter of high-stakes testing in the 1990s. As governor, George W Bush expanded its role and implemented a series of punitive measures, mostly focused on zero tolerance approaches. Since… testing motivates teachers to remove low-performing and disruptive students from class, suspension rates went through the roof – 95% of them for minor infractions. By 2009-10 there were 2 million suspensions in Texas, 1.9 million of which were for “violating local code of conduct” rather than a more serious offense. To deal with this onslaught of suspensions, for profit companies with close ties to state Republican leaders developed what Annette Fuentes calls “supermax schools.” These schools use fingerprint scanners, metal detectors, frequent searches, heavy video surveillance, and intense disciplinary systems to manage kids kicked out of regular schools. In many cases there is no talking allowed in hallways or lunchrooms. Teachers have little specialized training, and the low pay means fewer certified teachers than in the regular schools. The emphasis is on computer-based learning and frequent testing. Outside evaluations have been tightly controlled; the few external reviews have found terrible performance and prison-like conditions.

Overall, the claimed “Texas Miracle” of improved test scores was based on faked test results, astronomical suspension and dropout rates, and the shunting of problem students to prison-like schools outside the state testing regime. Bush rode this chicanery all the way to the White House, where he instituted it nationally in the form of the No Child Left Behind Act.85

Still, funding School Resource Officer programs continued to be a potential hurdle. While federal programs funded the creation of these programs, they generally shifted the cost to the city and district within two to three years. Already cash-strapped schools and cities then had to choose between police and books.

In Chapel Hill, NC, the city government increased the annual fee for having an SRO from $10,400 per officer to $25,400 per officer in 1997, forcing Chapel Hill HS to abandon the program.86 San Antonio Independent School District in Texas admitted that implementing a zero tolerance policy within the district would create “tough budget issues,” while in Victoria, TX, a zero tolerance program that would include SROs was dropped entirely due to the prohibitive cost.87

All this changed on April 20th, 1999, when two students went into Columbine HS armed with a variety of guns and bombs killing twelve students and a teacher before killing themselves. Columbine HS had armed security guards and video surveillance. It did not stop the massacre. 800 police officers including eight SWAT teams were on school’s campus. Students called from inside the school, letting police know that the massacre was still going on and providing real time information on where the shooters were. They did not stop the massacre. Police chose to frisk fleeing students instead. Later, a spokesman for the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Dept. explained, “A dead police officer would not be able to help anyone.” SWAT team leader Donn Kraemer added, “If we went in and tried to take them and got shot, we would be part of the problem.”88

Despite the armed guards, despite the cameras, despite the massive police presence choosing to “secure the perimeter” rather than confront the shooters, the message that was spun in Columbine’s aftermath was that schools needed more police. As Annette Fuentes recounts in her book Lockdown High:

Columbine was a human tragedy in a small Colorado town. But for school districts around the country it was a nightmare of what-ifs. For law enforcement it was a humiliation in which two disturbed teenagers with four guns and homemade bombs stymied the professionals. The reaction to Columbine by both sectors was dramatic and severe. Strict zero tolerance policies were ratcheted up tighter, security hardware was piled on, and policing became more militaristic, viewing students as potential enemies.89

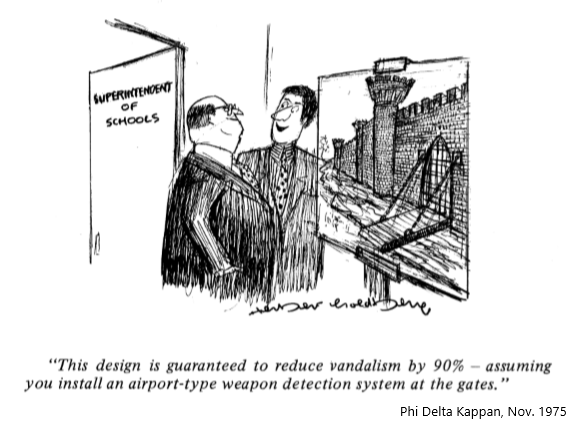

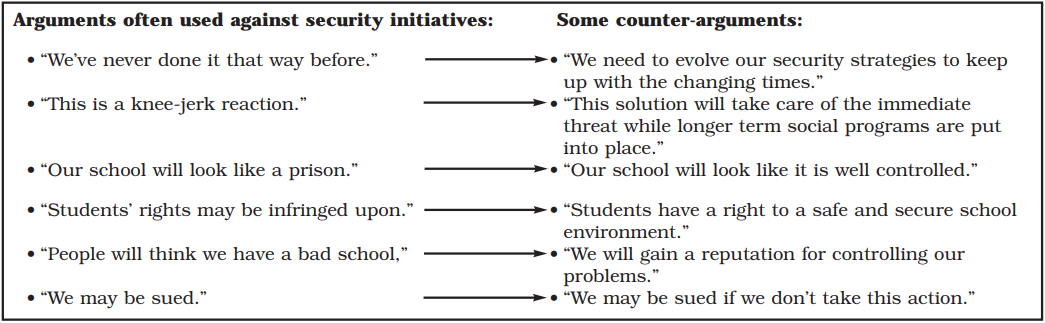

The National Institute of Justice (NIJ), the research arm of the Department of Justice, immediately commissioned Sandia National Laboratories to draw up a report on school security.90 While the report acknowledged that many school districts could not afford increased security measures, it pushed for them anyway. The report even provided districts and the security tech industry with a handy list of rebuttals to common complaints:

Mental health, bullying, easy access to guns, the structure of the school system itself; all of these causes of the Columbine massacre were completely ignored by the media and politicians. The story was too good and the windfall profits for the security industry too high for anyone to care. Instead of gun control, money rolled in to the armaments industry as police loaded up. According to a 2014 article in the Washington Post, at least 120 school police forces had requested and received military grade weaponry (M-16s, AR-15s, grenade launchers, and MRAP armored vehicles) through the government’s infamous 1033 program.91

Instead of mental health services or counseling or even books, schools spent lavishly on security tech and hiring more police.

Speaking of the National Association of School Resource Officers, Alex Vitale observes, “Its annual convention is a panoply of military contractors trying to sell schools new security systems, train officers in paramilitary techniques, and make the case that students are at constant risk from themselves and outsiders.”92 Annette Fuentes quotes the keynote speaker at the 2007 convention at Disney World in Orlando:

You’ve got people in your schools right now plotting a Columbine. Every town, every university now has a Cho [Virginia Tech shooter], we have al Qaeda cells thinking of it. Every school is a possible target of attack… You’ve got to be a one-man fighting force… You’ve got to have enough guns, and ammunition and body armor to stay alive… You should be walking around in schools every day in complete tactical equipment, with semi-automatic weapons and five rounds of ammo… You can no longer afford to think of yourselves as peace officers… You must think of yourself as soldiers in a war, because we’re going to ask you to act like soldiers.93

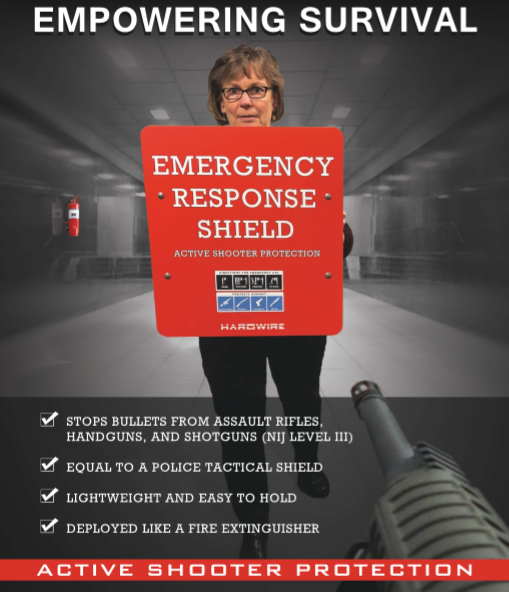

In Police Magazine’s 2018 special report on policing in schools, the table of contents shares a page with the ad index. In fact, the issue is mostly ads targeting the police readership. The ads include an app from Omnigo that allows students to anonymously snitch to campus police, a robot from Knightscape that drives around the campus providing a mobile surveillance platform for SROs, and, my personal favorite, an “emergency response shield” that, placed next to the fire hydrant, would allow teachers to confront active shooters just like Captain America.94

Panic following Columbine also provided police with an opportunity to delve even deeper into their fantasies of urban warfare. Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater Security, even built a training facility for police to re-enact their Columbine fantasies. From Prince’s biography:

Within six weeks of the Columbine shootings, Blackwater was home to a sixteen-room steel building that allowed for live gunfire inside, and even explosions outside for practice with “dynamic entry.” There was a sound track of alarms, and people screaming. We called the massive structure “R U Ready High School...”

We had actors playing students, covered in blood and pleading for help. Backpacks contained mock bombs; “shooters” hid among the “students” to lie in wait for police. It was a grisly scene, intentionally so – the sort of thing critics point to when they call us callous for using tragedy to grow the company. They don’t get it.95

In case this seems like the actions of a singular super villain, in 2019, the Indiana State Teachers Association had to push for an amendment to a school safety bill that would prohibit the firing of projectiles at school employees or students during any type of drill or training. The amendment was requested after police carried out an active shooter training drill at an Indiana elementary school. During the drill, police lined teachers up facing a wall and shot them with plastic pellets to simulate a mass execution.96 It is unclear what the value of this training was other than to play out the fantasies of the police officers involved – police who carry guns inside these schools.

All of the gear purchased during this unrestrained build-up, all of the surveillance equipment installed, all of the police added to schools at the expense of teachers, staff, and material has not stopped a single school shooting. In fact, the build-up has coincided with a rapid increase in the number of school shootings across the country. Yet, this is something that no one in the press or in politics has spent much time worrying about. “What about Columbine?” has served as the skeleton key to open up local, state, and federal budgets, diverting money from education to the security state and the industries that supply it. In short, Columbine has been a bonanza, making many people very rich.

The build-up has also worked to normalize the police state for millions of Americans. As Annette Fuentes notes, “With a total public school population of some 26 million, simple math says that for millions of children, being scanned and monitored has become as much a part of their daily education as learning to read and write.”97 Along with normalizing the surveillance state it has also worked to normalize police violence against students and teachers, not just for students and teachers, but for the police as well.

Violence in the Schools

More than ten years after the Stratford High School raid, another incident of police violence at a South Carolina school raised questions about the role of police in education. On October 26, 2015, video surfaced of sheriff’s deputy Ben Fields slamming a sixteen-year-old girl to the ground and dragging her across the floor after she refused to give her teacher her cell phone. The assaulted student — who suffered a broken arm, bruised ribs, back and neck injuries, and facial abrasions — was then arrested, along with a female classmate who spoke up and questioned Fields’ resort to violence during the assault.

Racists like Ted Nugent — who compared the student to “an animal” and said she “had it coming”98 — came out in support of the police with characteristic victim blaming and misdirection.99 Meanwhile, mainstream outlets commenced their usual dance of equivocation, hand wringing, and impotent calls for reform.100

Later that school year, a video surfaced showing San Antonio school resource officer Joshua Kehm body-slamming 12-year-old Rhodes Middle School student Janissa Valdez101. Valdez was talking with another student, trying to resolve a verbal conflict between the two, when Kehm entered and attacked her. “Janissa! Janissa, you okay?” a student asked before exclaiming, “She landed on her face!”102 In a statement on the incident, co-director of the Advancement Project Judith Browne Davis wrote, “Once again, a video captured by a student offers a sobering reminder that we cannot entrust school police officers to intervene in school disciplinary matters that are best suited for trained educators and counselors.”103

Videos of the attacks in San Antonio and South Carolina went viral and led to appropriate outrage. Yet, most police attacks on students go relatively unnoticed. How many people know about the video of a school resource officer in Round Rock, Texas who choked and then threw a 14 year old boy to the ground?104 The officer was cleared of any wrong doing despite the video evidence. Who remembers the Omaha school resource officer who was caught on tape repeatedly punching a student in the face after breaking up a fight?105 Or the surveillance footage from a Florida middle school that shows a police officer shove and throw a 13 year old student to the ground while fellow students and administrators watch passively—apparently just another day at school?106 Or the Kentucky SRO that punched a 13 year old student in the face for cutting the lunch line only to choke another student until he lost consciousness five days later?107 Or the North Carolina SRO who body slammed an 11 year old to the ground before dragging him across the floor this school year?108

Few recall that a decade ago, San Antonio was the home to another tragedy involving a school resource officer.109 As school let out on November 12, 2010, Derek Lopez, a 14 year old student at the Bexar County Juvenile Justice Academy—an alternative school for students that have been expelled from their regular school – approached a 13 year old classmate at the bus stop striking him once in the face with the back of his hand. The student would later state, “He just hit me once. It wasn’t a fight. It was nothing.”

Northside Independent School District SRO, Daniel Alvarado, witnessed the incident from his car and demanded Lopez freeze. Lopez ran and Alvarado chased after him in his squad car falsely telling a dispatcher that he had seen “an assault in progress. He punched the guy several times.”

After initially losing Lopez in a nearby neighborhood, Alvarado was told by his supervisor to “stay with the victim.” The SRO immediately disobeyed the order, setting off in his car to continue searching for Lopez. This was nothing new for Alvarado, who had a long history of insubordination that had led to four suspensions and warnings of impending termination.

A homeowner called the police after seeing Lopez climb over her fence and go into her shed. Alvarado arrived shortly after hearing the call go out on the radio. According to the homeowner, he charged into her backyard with his pistol drawn. Forty-five seconds later a single gunshot rang out, and Derek Lopez was dead.

“The suspect bull rushed his way out of the shed and lunged right at me,” Alvarado would later explain, “The suspect was literally inches away from me, and I feared for my safety,” An autopsy later revealed that Alvarado was lying.

He claimed that he immediately provided CPR, but the homeowner reported that the SRO carried Lopez’s body from the shed and dumped it on the grass. She, and a paramedic who lived next door, were the ones who tried to resuscitate the child while Alvarado watched “a little dazed and distant.”

The death of Derek Lopez—or another student like him—was inevitable. As inevitable as the city’s refusal to charge Daniel Alvarado for murdering Lopez. As inevitable as the $925,000 settlement that Lopez’s mother would reach with Northside Independent School District in exchange for dropping her wrongful death lawsuit.110 Armed police in the streets regularly injure, maim, and kill. When those same police bring their guns into the classroom it is only a matter of time before someone gets killed.

The School to Prison Pipeline and the Move to End SRO programs

As police moved into public schools, many white families moved out. In 2014, for the first time in US history, the majority of kids in the public school system were non-white.111 Meanwhile, whites make up nearly three-quarters of the student body at private schools.

Class and race are deeply intertwined in the United States, and shortly after the news that a majority of public school students are non-white came reports that 51 percent of public school students are living in poverty.112

For the last forty years Americans have been living through a period of stagnating wages and skyrocketing income inequality. Social programs have been slashed in favor of more cops on the street. And incarceration rates have skyrocketed, because imprisonment is how America controls its poor.113

It is in this context that school police must be placed. School resource officers are not there to protect students, but to police them.

Schools with a majority of poor and non-white students are the most likely to have a police presence.114 Once inside schools, police enforce zero-tolerance policies, giving kids a jarring introduction to the criminal justice system.

A study by law professor Jason Nance shows that schools “appl[y] zero tolerance to a multitude of offenses, including possession of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco; fighting; dress-code violations; truancy; and tardiness.”115 For example, dozens of students of all ages in states all over the country have been arrested on charges ranging from assault to inciting a riot for having food fights at school.116 States are criminalizing behavior that previous generations would simply consider the trials and tribulations of growing up.

After examining the latest data from the Department of Education, Nance concludes that “not only is there no evidence that zero tolerance policies have made schools safer, these policies have pushed more students out of schools and have created conditions whereby more students become involved in the juvenile justice system.” And the numbers are staggering. During the 2015 school year more than 290,600 students were referred to law enforcement agencies or arrested.117

Because predominately non-white schools are particularly over-policed, people of color are far more likely to find themselves caught up in what has come to be called the school-to-prison pipeline.

A host of studies118 confirm that black students are much more likely than their white counterparts to be suspended or expelled, and are much more likely to be arrested or referred to police for misconduct at school. In the 2015 school year, white students made up 49% of enrollment but accounted for only 36% of referrals to law enforcement and arrests. Black students made up 15% of the student population, but accounted for 31% of students pushed into the criminal justice system. Black girls made up 16 percent of the female population, but make up 39% of arrests.119

A 2019 report from the ACLU paints a stark picture of the American school system:

- 1.7 million students are in schools with police but no counselors

- 3 million students are in schools with police but no nurses

- 6 million students are in schools with police but no school psychologists

- 10 million students are in schools with police but no social workers

- 14 million students are in schools with police but no counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker120

The report goes on to point out that only 18 states met the recommended student-to-nurse ratio as determined by the American Nurses Association. Only three states met the student-to-counselor ratio recommended by the American School Counselor Association. And not a single state met the student-to-social worker ratio recommended by the School Social Work Association of America.

Schools have been systematically defunded – not just through property tax schemes, cuts in federal and state funding, neoliberal programs like No Child Left Behind and Every Child Succeeds, the funneling of public money into private and charter schools, etc. but by taking what little money is still left in school budgets and siphoning it off to already bloated police budgets. In short, the security state is drinking public education’s milkshake.

For decades groups have been railing about the school to prison pipeline and the increasing role of police in the everyday functioning of schools. And for years, politicians, Democrat and Republican, have been able to shrug off these efforts by pointing to the latest school shooting and fear mongering on what would happen if the police pulled out of schools.

But we are in a moment right now. The murder of George Floyd – caught on a cell phone video camera like so many other police murders – in the midst of a national pandemic exacerbated by the gutted neoliberal state that has left 40% of workers unemployed, has exploded a powder keg in this country. Rather than appeal to the same liberal politicians that have failed them over and over again, the people of Minneapolis took action and burned down the Third Precinct where George Floyd’s killers worked.

Now that people are in the streets threatening the very security forces that the state and capitalist class relies on, reforms that were previously deemed “politically impossible” are being seriously discussed by city governments.

Within days, Minneapolis Public Schools terminated its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department.121 Shortly after, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler, declared that he would discontinue all programs that put Portland PD in public schools.122 Now Denver will vote on removing police from its schools this week, with many expecting them to terminate their SRO contracts.

This is an unprecedented setback in the growing police occupation of American schools, a process that has continued relatively unabated since 1968. In early 2019, I wrote an article for Jacobin about the youth outreach programs that schools use to train students on how to interact with the police.123 I argued that not only was this blaming the victim for police violence, but it was shifting the onus for avoiding deadly interactions with police from the ostensibly trained adult professional – the cop – to children. An unconscionable act.

Many good meaning people criticized the article asking, “What else are we supposed to do? People are dying out here.” In March of 2019, the police were still an unbeatable political and brute force. I might as well have been trying to wish away a hurricane – a sentiment that I was definitely sympathetic to. Yet, nine months later, in Minneapolis, a chink in the armor was revealed and now everything is possible again. Now is the time to demand police out of schools as a starting point on our way to defunding, disarming, and disbanding.

If we stay in the streets, the future is ours!

- “SRO Program Unconstitutional?” The Phi Delta Kappan (Vol. 48, No. 10, June 1967), 539.

- Donald Robinson, “Police in the Schools,” The Phi Delta Kappan (Vol. 48, No. 6, Feb. 1967), 279.

- Christian Century, “Police in Schools,” 7/13/1966.

- Quoted in: Donald Robinson, “Police in the Schools,” The Phi Delta Kappan (Vol. 48, No. 6, Feb. 1967), 279.

- “School Duty for Policemen Under Study,” LA Times, 11/5/1968.

- Johns Harrington, “LA’s Student Blowout,” Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 50 No. 2, Oct. 1968, p78.

- LAT, “Student Disorders Erupt at 4 High Schools,” 3/7/1968.

- LAT, “Brown Power Unity Seen Behind School Disorders,” 3/17/1968.

- LAT, “Demands Made by East Side High School Students Listed,” 3/17/1968; LAT, “Board Will Hear Demands from 4 East LA Schools,” 3/24/1968; LAT, “Student Disorders Erupt at 4 High Schools,” 3/7/1968; LAT, “But Won’t Remove Police,” 3/12/1968.

- LAT, “But Won’t Remove Police,” 3/12/1968; LAT, “Venice High Youths, Police Clash,” 3/12/1968.

- LAT, “Student Disorders Erupt at 4 High Schools,” 3/7/1968; LAT, “Here, Dr. Rafferty, Are Some REAL Urgencies,” 3/18/1968.

- LAT, “Student Disorders Erupt at 4 High Schools,” 3/7/1968; Johns Harrington, “LA’s Student Blowout,” Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 50 No. 2, Oct. 1968, p75.

- LAT, “1,000 Walk Out in School Boycott,” 3/9/1968; Johns Harrington, “LA’s Student Blowout,” Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 50 No. 2, Oct. 1968, p76.

- LAT, “Brown Power Unity Seen Behind School Disorders,” 3/17/1968.

- LAT, “School Duty for Policemen Under Study,” 11/5/1968.

- LAT, “City Council Will Act on School Officer,” 4/22/1969; LAT, “Police Officer to Take on Teaching Role,” 4/23/1969.

- LAT, “Plea by Schools’ Chief Angers Negro Leaders,” 7/18/1968.

- LAT, “Two Racial Incidents Flare Up at Schools,” 3/15/1969; LAT, “Pasadena High Dispute Solved but Pupils Rebel,” 3/20/1969.

- LAT, “Youth Day Students Involve Selves in City Controversy,” 5/14/1969

- LAT, “Student Behavior Held to be Better This Year,” 10/2/1970

- LAT, “School Duty for Policemen Under Study,” 11/5/1968

- LAT, “Glendale Approves SRO,” 4/23/1969

- LAT, “Wisecracks Fade as Campus Policeman Wins Admiration,” 1/11/1970

- LAT, “School Duty for Policemen Under Study,” 11/5/1968

- LAT, “Policeman May be Assigned to Racially Troubled Monrovia High,” 6/20/1972. Passed two days later: LAT, “City Votes for Campus Policeman,” 6/22/1972.

- Kristian Williams, “The Other Side of the COIN: Counterinsurgency and Community Policing,” Interface, Vol 3 No 1, May 2011, p90.

- NYT, “Disorders Erupt and Subside at High Schools Across Jersey,” 3/14/1969; “School Plans for Coping with Disorder,” Phi Delta Kappan (Vol. 51, No. 6, Feb. 1970), 334.

- “School Plans for Coping with Disorder,” Phi Delta Kappan (Vol. 51, No. 6, Feb. 1970), 334.

- “Kounsellor Kops: Berkeley Hi Up in Arms Over Ammo,” Berkeley Barb, Vol. 19 No. 18 Issue 430, Nov. 9-15, 1973, p5

- “Police Offed at Berkeley High,” FPS: A Magazine of Young People’s Liberation, No. 35, 3/1/1974, p27.

- NYT, “Somerset Schools to Get Police ‘Advisers,’” 10/28/1973

- NYT, “Police-in-School Plan Dropped,” 6/16/1974

- NYT, “Police-in-School Plan Dropped,” 6/16/1974

- “Police Survey: How Would You Make Schools Safer?” in Police Magazine SPECIAL REPORT: Keeping Schools Safe, 2018, p8-9.

- NYT, “Students Protest Weapons Search at Their School,” 11/11/1982

- NYT, “Students Protest Weapons Search at Their School,” 11/11/1982

- Ryan Archibald, “Traveling Dissent: Activists, Borders, and the US National Security State,” Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Washington, 2019, p227-228

- Ibid, 253-256

- Ibid, 239

- NYT, “Judge in Boston Defied on Busing,” 12/17/1974

- Jeanne Theoharis, A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2018), 55-56. Boston Globe, “Mr. Ford Adds Fuel to the Fire,” 10/10/1974; Boston Globe, “Ford Stands by His Remarks on Busing,” 10/11/1974.

- NYT, “Candidates Express No Differences on Issue of Housing Segregation,” 4/24/1976

- NYT, “Students in Boston Searched for Arms,” 10/23/1974; NYT, “Black is Beaten in South Boston,” 10/24/1974.

- NYT, “South Boston Schools Shut in Clashes Over Stabbing,” 12/12/1974

- NYT, “Violence Flares at Boston School,” 12/11/1975